The First Days at an Italian Culinary School: A Journey into the Heart of the World of Pasta

For years, I have quietly dreamed of mastering the technical secrets of Italian cuisine, of immersing myself so deeply in its centuries-old traditions that they would become part of who I am.

Pasta and sauces may seem simple at first glance — flour, eggs, water, tomatoes, oil — but to cook them truly well, one must understand technique, the logic of flavours, history, and that subtle, almost intangible love that Italians pass down from one generation to the next through their food.

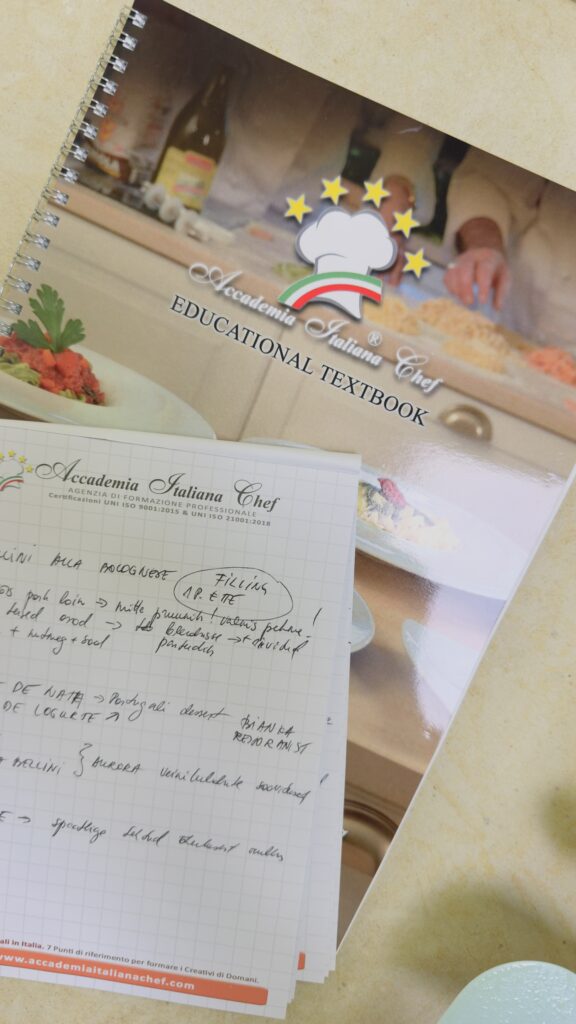

And so, at the muddiest time of the year in Estonia, I set my course for Florence to begin an intensive period of study. At Italian Chef Academy — the first international culinary school founded in Italy and now one of the country’s leading institutions for chefs. It is a school that attracts students from all over the world to study under masters of Italian cuisine.

With more than a decade of history, a faculty that includes world champions and award-winning chefs, and a strong focus on both technical mastery and ingredient-driven cooking, the Academy sets a demanding standard.

Just as my earlier learning and work have taken me to Japan, France, India, Greece, and Mexico, my next chapter in flavours now begins in Italy.

I chose Florence for its beauty. It’s easy to get around here, easy to eat well, there is so much to see — and to learn.

Our small group — an Estonian, a Portuguese, an American, a Canadian, and an Irish student — sounds like the beginning of a joke, but in reality we are all deeply connected by food and the restaurant world. We are guided by Auroraand Angelina, two women who combine precision and warmth in equal measure.

And that is exactly why the learning is so intense: five students means there is no escaping a single detail, a single technical movement, or a single insight.

“Forget everything you think you know about Italian cuisine,” we were told on the first morning. This is not a programme for amateurs, but for professionals who want to truly understand why things are done the way they are.

Where Does Pasta Come From — and Why Does It Split into Two Completely Different Worlds?

The story of pasta begins even before Italy. Ancient Greek and Arab cuisines were drying dough made from grain and water long before Italy turned pasta into a national symbol. Yet it was climate that ultimately shaped two completely separate worlds of pasta.

The arid, scorching heat of southern Italy was ideal for drying pasta. This is where durum wheat thrived, yielding golden, strong semolina. It was mixed with water rather than eggs, as eggs were a luxury for farmers.

This gave birth to firm, shape-holding pastas such as cavatelli and trofie — and, of course, to dried pasta as we know it around the world today.

n the north, the climate was different. Soft wheat produced 00 flour — the finest grind — which, combined with eggs, gave rise to delicate, silky, elastic fresh pasta.

Tagliatelle, ravioli, tortellini — everything we associate with craftsmanship and hand-made pasta emerged from Northern Italy.

100 grams of flour, 50 grams of egg — that’s the rule of thumb. But everything else is shaped by the humidity of the room, the temperature, and that indefinable “love” that determines whether the dough asks for more flour or more liquid.

According to our Italian instructor, pasta making is not something you can do by recipe alone. You have to feel it.

Why Is Fresh Pasta Always Better Than Dried Pasta?

When it comes to flavour and texture, the answer is simple: fresh. Fresh pasta is silky, tender to the bite, and full of character. It absorbs the sauce so completely that pasta and sauce are no longer two separate elements, but a single whole. It is a dish that doesn’t sit on the plate as individual components, but comes together as one.

Fresh pasta is also better for your body. It is easier to digest because it contains more moisture and less gluten, causes a gentler rise in blood sugar, and includes eggs, which provide protein, fats, and essential vitamins.

And most importantly — fresh pasta requires no additives whatsoever. It is as pure as food can be.

Dried pasta is often industrially dried at high temperatures. This alters the protein structure and makes it harder to digest.

Then we arrive at our first sauces. Our very first task is the simplest of all: tomato sauce. The tomatoes are briefly blanched, the skins removed. Olive oil is heated in a pan, finely chopped onion is added and gently cooked until translucent — only then does the garlic go in. And finally, the tomatoes.

What happens next is no longer technique, but time. The tomato sauce must simmer — slowly, gently, for at least two hours. This is when the tomatoes become sweet as the water evaporates and natural sugars concentrate. Acidity softens, flavours round out, and umami comes forward.

And now comes the moment that makes the day shine — mantecatura.

This traditional Italian culinary ritual is designed to transform a dish into something creamy, emulsified, and silky smooth.

Mantecatura is not simply “adding butter to a sauce.” You add the pasta — cooked for just a few minutes in well-salted water — to the sauce in the pan, along with a generous spoonful of pasta cooking water, and begin mixing rapidly using tongs.

Tossing or flipping the pasta in the pan, combined with air, heat, and constant movement, turns fat and water into a perfect emulsion. Mantecatura is the technique that gives a sauce its true flavour and structure, and it can be done even without butter — using only olive oil and pasta water.

Key Insights from the First Day

Today I learned that when making pasta, it is never left to rest on a table or tray — that’s what a pasta rest is for. Pasta is never hung; hanging breaks its structure. Pasta is never finished cooking in the pot — the final minutes must be spent in the sauce, in the pan.

Pasta water should taste like the sea — properly seasoned with salt; soffritto must never be browned, only gently softened; and al dente is not a matter of Italian temperament, but a technical principle.

Al dente does not mean “a bit hard.” It means that the pasta is soft on the outside, with a gentle resilience at its core. Inside, there is a small anima — the soul of the pasta — not raw or hard, but a pale line at the centre.

This texture allows the pasta to absorb the sauce more effectively, release just the right amount of starch, and be digested more slowly.

One of the biggest realisations of the first day wasn’t about pasta at all, but about my own life. Working in a kitchen is physical — heat, heavy lifting, bending, stretching, standing for long hours without a break.

And being there, I felt just how much all the trails I’ve hiked have prepared me for this.

When you’ve spent hours moving under the blazing sun with a backpack on your shoulders, learned how to breathe, keep your pace, and keep going even when your muscles begin to protest, you can also stay on your feet longer in the kitchen.

The heat of the stove, heavy pots, a fast rhythm — it’s the same physiology. Hiking doesn’t only teach you how to move in nature. It teaches you how to tolerate discomfort, stay focused, and not give up.

That evening, nine hours after the day had begun, some of our group sank down from sheer exhaustion, unable to move any longer. Gianni and I finished washing the last dishes and turned off the kitchen lights.

And I felt that familiar sensation from mountain hikes — that our bodies are capable of far more than we believe.

A New Week, New Dishes, New Techniques, New Discoveries

I believe that after the first part of My Italian Kitchen, you will never finish cooking your pasta entirely in the pot again, never rinse it under cold water, and never rely solely on the timing printed on the package. You will taste the pasta and feel the dough with your hands.

Fewer components mean more flavour and better emulsification, and pasta water will never again be forgotten in the sauce. Just as Italians do — and just as it is taught in Florence, where pasta is not spoken of as mere food, but as culture.

You can read My Italian Kitchen II here.